How to Value Pre-Revenue Startup Companies with Highly Uncertain Future Operations

By Matthew R. McCranor, ASA

In general, financial theory states that the value of any given company should be equal to the present value of its future income streams. For publicly traded companies, investor expectations of future performance are inherently reflected in each company’s stock price. For private companies, valuations are often determined by a professional business appraiser, who may apply a number of different approaches and methodologies in order to make an informed conclusion of value. This process

But how, then, do you determine the value of an early or development-stage company that has yet to generate any revenues, and for which future operating results cannot be accurately estimated? Luckily for us, scholars, investors, and business appraisers alike have pondered this question intently over the years so we don’t have to. During the remainder of this article, we will highlight some of the more common approaches and techniques that have been used to value interests in such early-stage companies. Importantly, we note that each of the approaches and techniques highlighted will provide an indication of the “pre-money” valuation of the subject company (as a going concern) – that is, the value of the entity immediately before an investment is made therein.

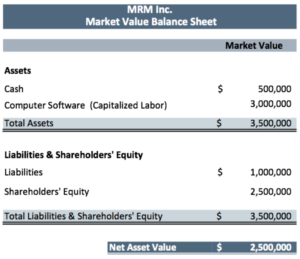

NET ASSET VALUE METHOD

The first, and often simplest, way to determine the value of a pre-revenue startup is to calculate its net asset value (“NAV”). Though used most often in appraisals of real estate of securities holding companies, this method may provide a reliable indication of value for certain types of early-stage businesses, including software development companies. In practice, the NAV method involves computing the total market value of the subject company’s assets and then subtracting all outstanding liabilities from the result. By way of example, let’s consider MRM Inc., a fictional software company that is currently beta testing a new office software suite. The assets and liabilities of MRM are listed below. In determining the company’s net asset value, our first step is to “mark to market” the company’s assets. In doing so, we carry cash at its book value ($500,000) and adjust the cost basis of the company’s in-process software to reflect its market value. In this instance, the most reliable indication of the market value of MRM’s software is its replacement cost – or the amount that it would cost an unrelated third party to duplicate the software development efforts of MRM from scratch. After discussing with management, we have determined the software’s replacement cost to be $3.0 million. Consequently, MRM’s assets had a total market value of $3.5 million. Subtracting total liabilities of $1.0 million from this amount yields the net asset value of the company, of $2.5 million.

Application of the net asset value method is often fairly straight forward, providing an easy-to-derive initial indication of a pre-revenue company’s value. While often useful in the valuation of startup companies, the net asset value method does not give any consideration to future expectations, nor does it give any weight to the intangible qualities of the subject company. Consequently, it may be advisable to weigh the concluded NAV of the subject company against the output of one or more startup company-specific valuation methods. We will consider four of these startup company-specific valuation methods in the paragraphs that follow.

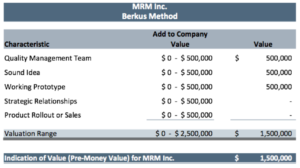

BERKUS METHOD

Frustrated with the imprecise way in which early stage companies were being valued, angel investor David Berkus developed his own method of determining value in the mid-1990s. This formula, most often referred to as the Berkus Method, has been refined by its creator over time, though its basic premise has remained the same. In essence, the Berkus Method involves assigning increments of value of up to $500,000 for each of five major risk-reduction factors present in the subject company, resulting in a pre-money valuation of up to $2.5 million. Importantly, Mr. Berkus notes that the model is only appropriate in cases where it is believed that the subject company, if successful, could achieve gross revenues of at least $20 million by its fifth year of operations.

Below, we apply the Berkus Method to our fictional subject company, MRM Inc. For illustrative purposes, we will apply the maximum incremental value of $500,000 for each applicable factor, though the smaller amounts may be selected if the appraiser or investor so chooses. Here, the company gets credit for having a sound idea, a quality management team, and a working prototype, but is assigned no value for qualities that it lacks, including strategic relationships or pre-existing sales. As a result, the Berkus Method suggested a value of $1.50 million in the case of MRM Inc.

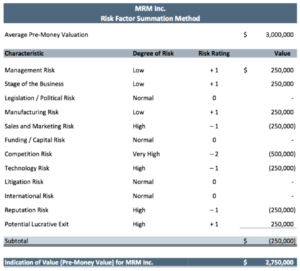

RISK FACTOR SUMMATION METHOD

The Risk Factor Summation Method is similar to the Berkus Method, though it expands the number of risk factors under consideration from five to 12, as seen in the tabulation below. In analyzing each factor, the appraiser considers the riskiness of the subject company compared to its industry peers, and then assigns an integer “risk rating” of between -2 (signifying very high comparative risk) and +2 (very low comparative risk). A “normal” or average risk rating would be assigned a risk rating of zero. The selected risk ratings are then multiplied by a valuation factor of $250,000; therefore, each factor has the potential to incrementally increase or decrease the company’s value by as much as $500,000. In order to determine the total value of the company, the sum of these resulting figures is then added to the average pre-money valuation of pre-revenue businesses in the subject company’s region. In the case of MRM Inc., the Risk Factor Summation Method suggested a value of $2.75 million.

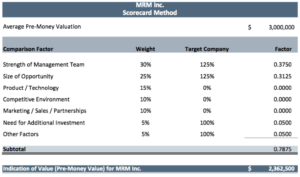

SCORECARD METHOD

Another widely used method for valuing pre-revenue startup companies is the Scorecard Method, which was developed by angel investor Bill Payne circa 2006. Perhaps the most detailed of the approaches outlined in this article, the Scorecard Method involves making a series of comparisons between the subject company and industry averages in the local market. There are seven comparison factors used in this method, and each is assigned a weighted ranking based on the contribution to total company value that the factor is assumed to have. In general, the strength of the company’s management team has the most significant impact on its value (accounting for up to 30% of the total company value), while the need for additional investment has the lowest impact on value (of up to 5%). The weightings selected below are typical for startup companies, though they may be adjusted based on the specifics of the subject company, its industry, local market, and any other relevant factors.

- 0–30% Strength of the Management Team

- 0–25% Size of the Opportunity

- 0–15% Product/Technology

- 0–10% Competitive Environment

- 0–10% Marketing/Sales Channels/Partnerships

- 0–5% Need for Additional Investment

- 0–5% Other

After selecting these comparison factor weightings, we next conduct an analysis of how the subject company compares to its industry peers in regard to each of the seven major categories. There are a number of worksheets available online for free, which may assist in this portion of the analysis. After conducting this analysis, weights are then assigned for each comparison category to represent how the subject company compares to its peers, with a weight of 100% representing roughly average qualities vis-à-vis industry norms. Each of these selected weights is then multiplied by the overall comparison category weighting, yielding a series of valuation factors which are added together to produce a single valuation factor. Finally, this factor is multiplied by the average pre-money valuation of pre-revenue businesses in the subject company’s region, yielding an indication of the total company value. In the case of MRM Inc., the Scorecard Method suggested a value of $2.36 million.

Y COMBINATOR

As evidenced above, the three most popular startup-specific valuation methods will generally indicate values of between $2.0 million and $3.0 million, regardless of the individual company specifics. Given the amount of time and effort to undertake a company valuation using these methods, it is not surprising that certain venture capitalists have decided to forego these types of analyses in recent years, and have instead adopted a single standard investment deal structure. One of these venture capital groups is Y Combinator (YC), a California-based seed accelerator founded in 2005. To date, YC has provided funding for nearly 1,500 startups.

In 2011, YC began making a standard investment offer to every company that it decided to invest in, regardless of the individual investment attributes of the companies. Initially, the standard investment deal involved YC issuing each company a $150,000 convertible note; this amount was subsequently reduced to $80,000 in 2013. In 2014, the company announced “The New Deal” for YC startups, revising its standard investment deal again. Through 2018, under this “New Deal,” YC has offered a blanket investment to each startup company of $120,000, in exchange for a 7% equity stake. As a result, between 2014 and 2018, the company effectively valued hundreds of startup businesses at an identical valuation of $1.7 million. Beginning in September 2018, YC increased its blanket offer for a 7% equity interest to $150,000; this implies a current static valuation for all startup companies of $2.1 million.

Admittedly, this is an extremely heavy-handed approach to valuing startup companies. However, it does provide actual evidence of how investors value development-stage companies in the real world. Moreover, the deal structure developed by YC does appear to line up with the range of potential values produced by the more detail-oriented methods and techniques described above. This observation may be entirely a coincidence, a “happy accident” stumbled upon by the author of this article. Perhaps, though, it hints at the fruitlessness of applying technical or detail-oriented techniques in the valuation of a pre-revenue startup company, for which the only certainty is the uncertainty of its future success.